The Mongolian Mining Journal /Oct.2020/

E. Odjargal

The Government is in a commendable hurry to fulfil the MPP’s election promise that banks would not be allowed to charge more than 1 percent per month as interest on their loans. But how effective would this be in reactivating an economy crippled by the pandemic and, more important, can this one step in isolation do much to heal a seriously fractured financial system?

Folllowing Parliament’s adoption in August of a policy to reduce the interest rate on bank loans -- to 12% initially and then according to the situation over the next four years -- the Ministry of Finance, Mongolbank and the Financial Regulatory Commission are jointly working on putting flesh on the basic idea to ensure the best results for all stakeholders. As of now, six amendments to the present law governing the issue are planned to be submitted to Parliament for approval in its fall session.

Speaking in the last session of Parliament – its first after the election - Prime Minister U.Khurelsukh said his government was committed to major reforms in the banking and financial system, aimed at loosening the stranglehold of banks, all of which are privately owned. Lower interest rates and easier access to loans would incentivize entrepreneurs, he said, and added that “a stable society” is possible “only when citizens have jobs and income, own apartments, and have an improved quality of life”.

If the sale of NOMAD bonds at the end of September raised $600 million, taking the foreign debt repayment pressure off the government, at least for next year, several other developments have not been so good for our economic prospects. The mining sector continues to have a most difficult year, failing to attract foreign loans and investment, and at the same time forced by the pandemic to reduce exports. The stagnation there has seriously affected the income of both entities and individuals who supply everyday goods and services to mining companies. Travel restrictions have stopped migration in search of better-paid jobs abroad. With all this, businesses with loans are under pressure to meet their repayment schedule, often with high interest.

Private commercial banks are not the sole financing source in Mongolia. There are hundreds of non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) and credit and savings unions (CSU), as well as pawnshops, all of which lend money to mostly individuals, who usually pledge their pension or salary as security. Some 70 percent of the total lent by banks to citizens are against a mortgage or salary. The mortgage programme was launched seven years ago, mainly to reduce urban air pollution by making it easier for ger district households to move into apartments. Unfortunately, despite the soaring number of mortgage loans, the number of ger district households has not gone down, but has actually increased.

Forcing banks to charge less from borrowers is only part of a bigger picture. Last year NBFIs and CSUs together lent MNT1.8 trillion to citizens, whose number doubled from that of such borrowers in the previous year. These loans do not come cheap. If banks charge a maximum of 20% per annum, the NBFI rate is easily 30% plus, which goes up to 60% plus at pawnshops, while individual moneylenders demand anything up to 80% per day. Their clients hardly ever know who owns an NBFI or a CSU or a pawnshop, but it is widely believed that many high-ranking state officials and politicians are actively involved in the usury business.

Part of the new lending policy would see commercial banks under public ownership and their shares traded in the stock exchange, with no individual or entity permitted to own more than 20 percent of the shares. Most Mongolian-owned commercial banks are believed to have around five investors, but their identity is usually secret. Banks that have foreign investment, individual or institutional, get actively involved, even if indirectly, in multiple sectors including mining, railway, energy, construction, property, car sales, and cashmere. In either case, a small coterie, usually with close ties to politicians, controls a vastly disproportionate part of our financial system – some put it at as high as 90 percent – and since only banks have the necessary monetary resources to lend to big projects, they face little or no competition.

One reason why banks lend at such high rates is that they pay high interest on their various savings accounts, usually held by a large number of small depositors. Lower lending rates would thus adversely affect these depositors, whose savings make the banks rich in the first place. During the discussion in Parliament, several MPs wondered if it would be fair to put the borrower above the saver. Interestingly, 10 MPs have declared that they each have more than MNT10 billion in bank savings, which earn 10.4 percent in average interest. That is, by any reckoning, a tidy sum.

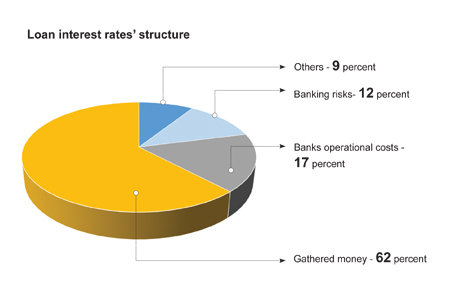

Even if most individual deposits are smaller than these, lower interest could be damagingly unpopular among depositors. If banks do not wish to take that risk, they would have to cut their costs, which include operational and administrative expenses, premises rental, salaries etc. These naturally vary from bank to bank, depending on things like how many branches they have. One way to effect savings could be by sharing costs for certain types of infrastructure, for example, by allowing several banks to be served by the same ATM and POS.

In the event that banks reduce the interest they pay to depositors so that they can afford to charge borrowers less, it is quite possible that large depositors would move their money elsewhere. That would support the new policy which wants banks to raise money from the stock exchange and not to rely on deposits. As for depositors investing in shares and not parking their money in banks, that goal can be achieved if the government makes income from bank interest taxable, and at the same time offer some incentives for investing in stocks. That would also help develop the stock market. The Mongolian Stock Exchange has already taken some steps to mop up citizens’ savings but a lot more can be done, given that banks at present hold MNT17 trillion belonging to individuals and entities. Some risk is always there but in general returns from investments in shares are more attractive than bank interests. In developed countries, companies raise 50 percent of their capital in the stock market but in our country it is just 4-5 percent. With no other institution matching their monetary resources, banks in Mongolia are well positioned to dictate their lending terms. This should change and can change if banks face competition from the stock market and the insurance sector. When a borrower has options, loan interest rates are bound to come down.

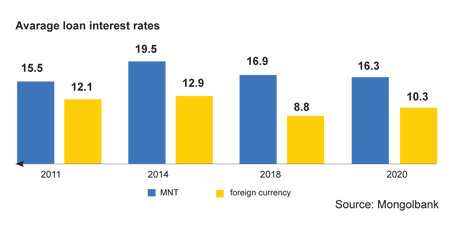

Three previous attempts were made in the last ten years to reduce loan interest rates, with varying success, but the general trend has been for commercial banks to charge less. In the last four years, the rate has come down by approximately 4 percent, for reasons such as macroeconomic stability, relatively low inflation, and export surge. It was in such a situation that the MPP decided to lower rates further, but perhaps that requires a rethink in the light of the debilitating impact of the pandemic on both the national and global economy, chaotic uncertainty ahead, foreign debt repayment pressure, and a likely slowdown in China’s industrial growth.

The decision has to be seen against the steady and unchecked depreciation in the value of the MNT. We see our economy as being twice the size it was ten years ago. At the start of the decade one US$ was equal to MNT1200 but now it has gone past MNT2850. The apparent growth in the size of the economy has to be seen against this fall, a result of which has been that many people have taken to save in US$ and not MNT. A very recent report says term deposits in foreign currency amounts to MNT 5.1 trillion, a whopping 74.7% increase year-on-year.

Reducing lending rates may be seen as an expression of the Government’s desire to see more economic activity, but what Mongolia needs is a comprehensive reform of its financial system. This is not a new demand, but gained traction when we were put on the FATF gray list. It is also a condition of the IMF Extended Fund Facility programme.

Remember when Mongolbank took administrative control of Anod Bank, after deciding that the nation’s fifth-largest commercial bank did not have the financial capacity to meet its obligations? This was some years ago but the background story still holds lessons for us. The government had floated tenders to build paved roads in rural areas and the selected companies borrowed money from Anod Bank at a high rate of interest. They did their work but were not paid by the government, forcing them to default on their bank loan repayment, thereby pushing Anod Bank into bankruptcy for no fault of its own. Another example of how political machinations destroy a bank’s financial viability is offered by the Development Bank which was established in 2013 mainly to provide loans to implement big projects of national importance. Such loans came to account for more than half of the total lending by the bank, but some parts of the loans have not been repaid until now, leaving the bank to flounder in “good” intentions and missed opportunities. To add to its woes, Capital Bank shut its doors in 2019, effectively shutting out Development Bank from the MNT300 billion it had kept there from its Pension and Health Insurance funds.

This year has seen the merger of Ulaanbaatar Bank and Trade and Development Bank, both of which had the same owner. The State Auditor General reported to the Fiscal Standing Committee of Parliament in August that another two banks are about to wind up operations. It was no surprise then that in a recent report the US Embassy says the IMF’s EFF programme has ended unsuccessfully, as little progress has been made in banking sector reforms.

All this makes one wonder if reducing lending interest rates is really as important as it is being made out to be. The real strength of the financial system lies in it being transparent and free from political interference, allowing fair competition. We import so much of so many things, while our export items are few and export destinations fewer. This lopsided foreign trade is the main reason for our currency depreciation and also, if indirectly, for the high costs of borrowing.

It was only in 2011, when our poverty level stood at 30 percent, that The Economist called Mongolia “the next Kuwait”. The most glaring example of our failure to fulfil our promise is that in the ten years since then, this has come down by just 1 percent. Rise in GDP, economic growth, size of economy – all this means little if inequality also increases, if the poor-rich gap keeps expanding. Stopping at lowering lending rates will not resolve the paradox of resources-rich Mongolia and its fragile economy.