B. Tugs

A recent study compared the investment climate between Mongolia, Zambia. Chile and Australia. It is not surprising that the latter two mining giant countries are far ahead of us in terms of mining investment and other related indicators. But don’t be surprised if Zambia stands higher than us.

It is very difficult to compare Zambia and Mongolia generally. The average person may imagine that Zambia is about a herd of elephants grazing on the African plain, while Mongolia is thought of as full of horses on the bitter cold steppe. Both are great scenery, but very different.

Zambia is landlocked like us, but borders eight countries in southern Africa. The country is one of Africa’s largest copper producers, earning US$6-7 billion a year from copper exports. It has four copper smelters and refineries, with a capacity of 1.2 million tons of finished products.

The Ministry of Mining and Heavy Industry has recently got a study to assess the investment climate in Mongolia’s extractive sector prepared by Adam Smith International and funded by EBRD. It was presented on 17 May 2022.

According to the Adam Smith report, Zambia’s mining sector was privately owned during British colonization, and after its independence in 1964. Between 1969 and 1974, the mines were nationalized. Unfortunately, copper prices fell between 1974 and 1975 and remained low for decades. In other words, Zambia has had a difficult time till copper prices started rising. In the 1990s, the mining sector was re-privatized. Currently, Zambia’s economy is heavily dependent on mining. As of 2020, this sector accounted for 11% of GDP, 80% of exports, and 31.4% of the state budget revenue. The country exports not only copper but also cobalt, gold, emeralds, manganese ore and alloys. Due to its abundant surface water resources, most of its energy comes from hydropower. There is also a 300 MW coal plant. In the future, large solar and wind projects are expected to come. Most recently, First Quantum Minerals has agreed with French and British companies to build a 430 MW solar and wind power plant in Zambia.

Zambia is relatively close to Mongolia in terms of investment inflow size, but recently Zambia has been working extensively to attract investment. Ron Smit, a senior analyst of the Adam Smith International research team for the study, said the government was working hard to regain investor confidence after elections in August 2021. Starting this year, mineral royalty tax is deductible in determining the taxable income of a mining company.

The results have recently become more apparent. A team led by the country’s President attended Mining Indaba 2022, a major mining investors’ event in South Africa in early May to announce that ‘Zambia is back’. The country’s president said two important points. The first was about zero tolerance for corruption and, second was about getting things done, not just speaking of the potential. First Quantum Minerals, a Canadian company that has been operating in Zambia for many years, announced at the conference that it would invest US$1.25 billion in the expansion of the country’s Kansanshi copper mine. At the same time, the company announced an additional budget of US$100 million for its new nickel project in Zambia. This event will undoubtedly help to create a positive investment climate there.

There are big companies working in Zambia, including Barrick Gold, Glencore and others, with state-owned ZCCM IH owning between 10 and 90 percent of their projects. The state-owned company’s policy is to increase its stake in projects at a time when the commodity market is booming.

In Zambia, steps have been taken in recent years to periodically change the royalty rate. This has hit mining companies in the country very hard, and even led to the situation where some companies approached arbitration.

The mining tax system has been a hot topic in Zambia since 2006. Subsequently, in 2008, royalties and other tax rates were increased. Indeed, in 2015, the country decided to increase copper royalties from 6% to 20% for open pit and to 8% for underground mines. However, the decision was soon overturned and the rate was set at 9%. Currently, Zambia sets a 5.5-10% royalties for copper depending on market prices. The royalties initially rose from 0.6% to 3% in 2008 and then to 6% in 2012. However, it surged to 20% in 2015, which deterred investors. Now it seems to be at a relatively “golden mean” percentage. When mineral prices are really high, it is fair and mutually beneficial for both parties to pay large sums to the national budget from the companies.

The country is heavily indebted to China, and the country is expected to attract more investment from there, Ron Smit said. However, the Zambian external debt situation is relatively good compared to Mongolia. The total Zambian debt is equal to its GDP, which is much lower than in our country.

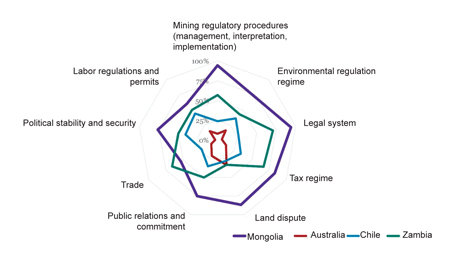

In the case of Zambia, the graph below shows that it has outperformed Mongolia in terms of policy and institutional fundamentals. According to Adam Smith’s research, Mongolia is not as competitive as Zambia in terms of attracting investment given those indicators.

GAP ANALYSIS: Policy and Institutional Factors

Our country has huge mineral resources’ potential, but it needs to improve its competitiveness to attract investment in the exploration sector by improving policy factors. Ron Smit emphasizes that these are indicators that can be corrected by internal efforts and are relatively independent of external factors. However, we should remember that Zambia’s tax environment is not much smaller than ours. In other words, it is not necessary to impose a low tax rate. For example, Zambia’s income tax (30%), withholding tax (20%), and VAT (16%, but some refundable) are close to or higher than ours.

One of Zambia’s problems is its high poverty rate: 60% of the population lives in poverty. According to some studies, this figure could be even bigger at 88%. Although efforts are being made to reduce poverty, tangible results are still far away. So what this shows is that foreign investment and the export of wealth may increase, but that doesn’t always mean that people’s livelihoods will improve directly. One big job awaits the country: currently Zambia does not have a wealth fund. Discussions on establishment of the fund took place, but without result.

In our country, poverty has also been increasing in recent years, despite it’s earlier decline during the mining boom till 2012. As for the Wealth Fund was our hope when it was established a few years ago . But as “Future Heritage Fund”, it is almost “empty” now because of child benefits paid out. Of course our children need food right now, but the future generation’s well-being must also be guaranteed. Thankfully, the government recently announced that a new law on the Wealth Fund is to be submitted soon. It will take at least ten years for the wealth fund to grow, and so we need to be hurry.

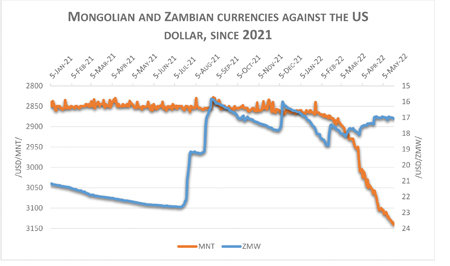

One interesting thing is that Zambia’s currency (kwacha) has appreciated sharply against the US dollar in recent months. This is because exports far exceed imports and there is a strong balance of payments situation. The currencies of major economies were depreciating against the US dollar, but Zambia managed to reverse the pattern. Zambia is actually a US$20 billion economy, and much bigger than ours. But the total population is almost 19 million. The country now has to work to reduce poverty dramatically and distribute its wealth properly.

In the case of Mongolia, the US dollar rate was relatively stable during the pandemic until recently. But as soon as March came, the problem started. In fact, exports are slightly higher than imports, but the situation is not good. The lesson from Zambia is that our country can get its currency rate against US dollar below the 3,000 threshold in the future. Also, a country can become a ‘super exporter’ of copper and other minerals, but poverty will not go away without a longterm-oriented wealth fund.