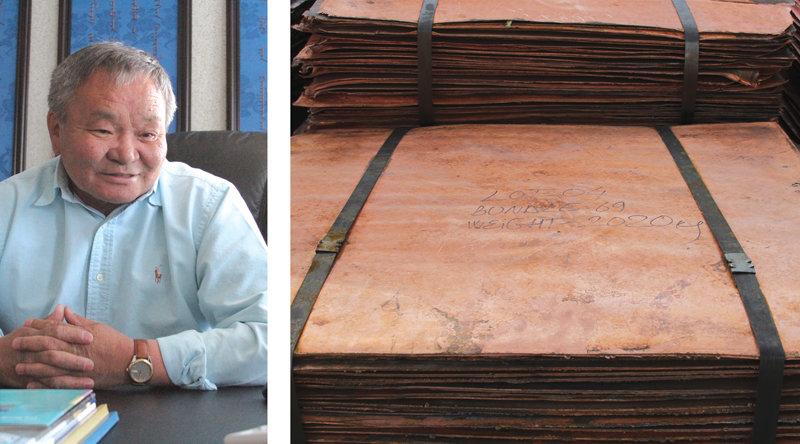

Erdmin LLC, recipient of The Mongolian Mining Journal Best Technology Award in 2013, was a pioneer in adapting the prevalent cathode copper production technology to Mongolian climatic conditions. An Honoured Industrial Worker of Mongolia, Dr. J. Damdinjav played a very large role in setting up Erdmin, where he was Executive Director and Director General. Currently a consultant to the company, he traces the history of Erdmin in this conversation with G.Iderkhangai and talks about old times with nostalgia.

Did you start your working life at Erdenet Mining?

My father crafted nice items from copper and silver and out of admiration for his work, quite early in life I decided to be a metallurgist though in those days I understood the profession as that a gold refiner. When I finished school I was lucky enough to be among those chosen to study non-ferrous metallurgy in the Soviet Union. I attended the Mining Institute in Leningrad from 1975 to 1981, and when I came back to Mongolia, the Government sent me to work at Erdenet as a mining engineer/metallurgist. I worked in several departments there in various capacities until December 1992, when I and several others were sent to the US for further studies. I took a special course in economics and English language at Colorado University and then majored in business administration. Earlier, I had attended the Management Development Institute in Mongolia and am one of the first graduates from there.

I believe you were one of the few technical professionals who spoke English when Mongolia adopted the market economy, right?

Yes. Thinking that knowledge of English would help in the world of market economy, I learnt it on my own and then joined the English training course that Erdenet used to organize for its employees at that time. Among the others who attended such a course, Purevee and Tserennadmid were sent with me to the US. After completing our study there in 1994, we came back to Erdenet and worked at its Foreign Trade Department. I was in charge of setting up new projects such as the sodium sulfate or the molybdenum burning plant and Erdmin. From 1995, as decided by Sh. Otgonbileg, then CEO of Erdenet, I worked solely for the Erdmin project, and was involved in a big way with its construction, development, commissioning, and then management. I discovered in the US that cathode copper can be produced by using a hydrometallurgical method. I signed an agreement with an American geologist, Richard Morris, on establishing a joint venture plant and I was appointed its Executive Director. Some 20 American specialists were involved in the work, and constant interaction with them improved my English considerably.

In those days, all who were sent to the Soviet Union for studies had to work for their sponsors when they came back, no?

As I recall, about 400 students went to study in the Soviet Union under agreements with what was then the Ministry of Fuel, Power and Geology. I joined Erdenet and worked as a crusher operator, walking with a hose in my hand and wearing Russian working boots. Once when a relative of mine saw me like this, he was very disappointed as he had expected me to be in formal and elegant clothes. Those days, someone with a professional degree received a good salary. I was paid MNT850. As a fresh graduate, I had much to learn and it helped that I started from the basics. Now, of course, I am a man of long experience. I learnt much from the Russians. Our Erdenet was a new city of youthful promise. “The Erdenet Ovoo is the face of this century” was a very popular song, and justly so. It is still great and colourful. My family still lives there.

Which other Mongolians do you remember who graduated from the Leningrad Mining Institute and then worked successfully in the mining sector at home?

There were many of us there, including N. Nyamtaishir of MAK, G. Sharkhuu, a metallurgist and Advisor to the Ministry of Mining and Heavy Industry, R. Delger, and L. Bataa, who graduated from Donetsk Mining Institute. Many of those who studied maintenance or metallurgy or mechanics came and worked at Erdenet, which in many areas was the best of its kind in Asia. When we came there, it used to process 16,000 tonnes of ore. In 1990, when the self-grinding workshop where I worked as deputy director, came into operation this rose to 20,000 tonnes. As young specialists we competed with one another for recognition of our knowledge and skills, but this was always in a friendly spirit. The most coveted award of our time was a letter of appreciation from the Ministry of Non-Ferrous Metallurgy of the USSR.

Now things have changed. If something started by someone proves to be successful, others would try to scuttle its progress. My fellow student at the Leningrad institute, Purevee, was also at Erdenet with me. He worked on setting up the molybdenum burning plant which made the third oxide of the light hard metal the second one, a matter of great importance. The plant worked for a while but then was closed down for political reasons.

Did you find any difference in terms of skills and competence between metallurgists in the western countries and those who worked at Erdenet?

There are no differences. Mongolians can work anywhere with the knowledge of metallurgy and the skills they have.

Tell us how Erdmin was set up.

Erdenet wanted to more fully utilize its mining resources, and so set up Erdmin as a joint venture with Americans. Mongolians were hired and trained to use the new technology, the special thing about which was that we were able to modify what was followed in the warm and hot climate of the USA and Australia to suit the very different Mongolian conditions. It began as a pilot plant but gradually became fully commercial. The initial capacity was to produce 2,500 tonnes of cathode copper per year but we had plans to raise this to 50,000 tonnes with time. However, Achit Ikht company came up and was allowed to use the second ore stockpile. I am not sure if it was a good idea to have a new company instead of letting an existing company grow, but in Mongolia it is now accepted that when political control changes hands, projects under implementation are switched off and new ones taken up.

Erdmin had very big ambitions, and a feasibility study was made on the ultimate target to produce 50,000 tonnes of cathode copper. We borrowed $7 million from Marubeni to establish the plant and were able to repay the entire principal amount by 2005, with the interest waived. The fees for services obtained from Erdenet were fully paid off in 2006. These settlements were made easier as the copper price was high at the time. It seems Erdmin is the only company which paid off such loans, demonstrating that our pilot plant was commercially viable. However, it remains a small plant, as no expansion has ever been made. The trouble now is that we are getting less ore from Erdenet, with which we have a 40-year agreement for supply of waste ore.

How much stock do you have?

We have enough for one year. Our agreement with Erdenet is for it to sell us 10 million tonnes of ore, but the matter cannot be taken up by the Government, as a similar dispute with Achit Ikht is in court. If we get the 10 million tonnes, we can operate for another 10 years. At present, the largest investor in Erdmin is RCM Company, which holds 58.5 percent of Erdmin stock, with Erdenet holding 25 percent, Mega Holding, a Mongolian company, 10 percent and J. Damdinjav the remaining 6.5 percent. In 2005, the plant recouped all its investment costs and I was rewarded with these shares. In 2010, I reduced my work load for health reasons, and restricted my responsibilities to working as a Consultant. Baatar, who had been with Erdmin, was made Director General. We now have 120 employees.

We produce and export about 2,500 tonnes of pure cathode copper and sell 3 million metres of copper wire of more than 41 types in the domestic market per year. We are the first in Mongolia to make value added industrial products. In 2005, we started with producing copper cables, and in 2011 moved on to making thinner wire -- called soft wire in trade -- and soft cable. Last year, we started to produce copper tape. Value is added every time copper is made into wire or tape.

Do you export the copper wire?

No, all our products go to meet domestic demand, which is large enough to also import Russian, Chinese and Korean cables. In that way, even though we do not export, we help substitute imports. Actually, it was the nature of the domestic demand that encouraged us to go for value addition.

We would like to make copper pipes and have repeatedly asked for reduction of related taxes but the Government does not respond favourably, maybe because importers of cables from Russia and China have a strong lobby. There is unfortunately no legal obligation for the Government to support national producers.

Who are your main buyers – individuals or economic entities?

Mainly, they are construction companies. Erdmin has its own store in Ulaanbaatar.

You are known to be the first Mongolian to try to sell pure copper at the London Metal Exchange. How did this come about?

I wanted to have a hand in setting the international copper price so that Erdmin could settle its debts early. At that time it was very important to be registered at the London Metal Exchange, as that would allow our products to be sold everywhere. We made some progress in our bid with a pilot project but Erdmin could not be registered as its production was less than the minimum stipulated 10,000 tonnes per year. As our company is not registered, we have to sell our cathode copper at $75 less per tonne. We sold it to Marubeni to pay off our debt and also to Samsung of Korea for six years. We also sold to Chinese buyers but stopped it after two years, to go back to Samsung. Noble company also buys from us.

Should Mongolia have a copper smelting plant?

It is essential to have one. Those who say it will cost too much and harm the environment, should know that no country can develop without heavy industry. Mongolia exports raw materials and imports finished goods. We have to go for value-added production but as the domestic market is small, this must be export-oriented. A large copper plant must have a smelter nearby, even if small. European countries have started to use copper in plumbing, and our country can very well make copper pipes. Electric cars will have a lot of copper in them. I want the copper smelting plan to be in Erdenet City, which has good infrastructure, water sources and transport network.

In the old days Mongols were skilled metallurgists but what happened to the processing tradition?

Historical documents and artifacts clearly demonstrate that Kidan and, before it, the Hunnu Empire used metals that had been well processed. Also to note is that several popular Mongolian names come from the word for metals or alloys such as iron, gold, silver, bronze, and steel. People name their children only after valued objects. Right from the great khagans -- Togoontomor (cast iron), Olziitomor (Ulzii iron), Ulsbold (Uls steel) etc. – to recent Prime Ministers -- Altankhuyag (Golden Armour) and Khurelsukh (Bronze Axe) -- Mongolians have borne names that show ours is a country which is very rich in minerals. What we need is the right policies to utilize them to benefit its citizens.