IntroductionThis is the first edition of the Mongolia’s Coal Industry Report from MICC. The following topics will be covered in the report:

Production and Infrastructure.An overview of the current and historical figures as well as specific issues surrounding resource estimation, production and transportation.

Mongolian Politics and Mining.An overview of the current political situation in Mongolia in the context of mining.

Coking Coal Demand and Prices.Our analysis on the demand on Mongolian coking coal, and MICC’s price outlook. (included in the full report)

Companies.Brief introduction to the equity investment possibilities in the Mongolian coal mining sector, covering both domestically and foreign listed companies, as well as the major non-public players in this market. (included in the full report)

Production and Infrastructure

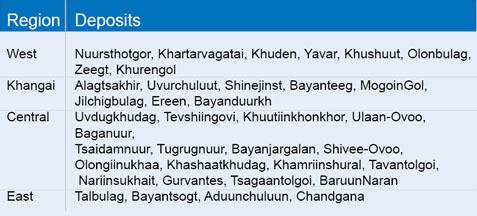

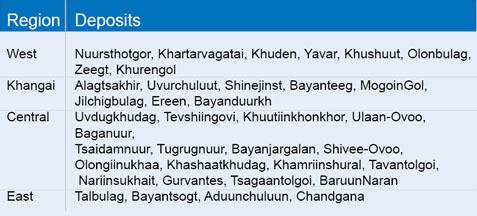

Mongolia’s Coal Resources and ReservesMongolia has over 300 known coal deposits with an estimated 152 billion tonnes of coal resources. Of these, detailed geological studies have been completed at about 80*. Companies with coking coal deposits attract the most attention, as their products are exported at considerable profits. The following table contains the major coal deposits in Mongolia in different regions as per the Ministry of Mineral Resources and Energy classification. Please see the last part of this study for more detailed introduction to each company.

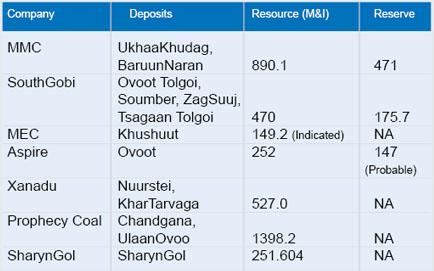

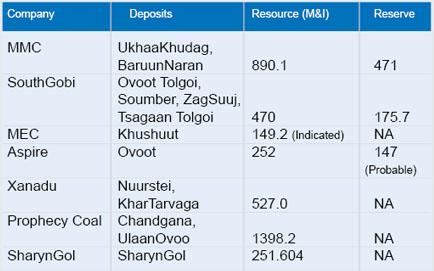

In the following table, we have listed the JORC and NI 43-101 compliant resource and reserve estimates for the companies mentioned in this report. From the coal mining companies listed on the MSE, only SharynGol (MSE: SHG) has announced its JORC compliant resources so far, although the rest have resource and reserve estimates classified in the Mongolian system.

Historical Production

Mongolian coal mines gradually shifted toward the modern industrial production methods between 1940 and 1970. However, formal resource estimations, tests for coking qualities and modern geological studies were not conducted until the late sixties. However, even at the turn of the twentieth century, Russian geologists had published their observation of some of the most famous deposits today, such as Tavan Tolgoi, EgiinGol and Choir. During the twentieth century, open-pit coal mines were created in almost every aimag so that Mongolia’s domestic demand for thermal coal was completely met2 .

In 1993, the geologist D. Bat-Erdene and Tuya estimated that Mongolia has over 152 billion tonnes of coal resources. Since then, many private companies have entered the country, and many have completed the Australian JORC or Canadian NI 43-101 compliant resource and/or reserve estimations. The total coal resource estimation is expected to rise according to most experts, as more detailed geological surveys are completed.

Mongolia’s coal production has been on the rise since the troubled 90’s, when nearly all enterprises, including coal mines, suffered due to the instability of the transitional economy. The total amount of coal mined in Mongolia began to grow rapidly after 2004, which is about the time the current resource boom and the export rush started. In 2011, the total production was at 32 million tonnes, and over 66% were for export.

Total Mongolian Coal Production and Export![]()

In the first seven months of 2012, Mongolia mined about 14.3 million tonnes of coal, which is 7% less than the production in the same period in 2011. Many of the mining companies are reporting lower-than-expected coking coal prices and lower sales for the first half of 2012. This is mainly attributed to the Euro-zone related global economic slowdown, and the cooling of China’s steel production.

The domestic coal consumption had stayed more or less constant, between 5-6 million tonnes per annum, between 1991 and 2008. In 2009, when the domestic consumption reached 7 million tonnes, it had finally reached the recorded level in 1990. Since then, the domestic total consumption grew to 11 million tonnes in 2011. During this period of growth in domestic consumption, Mongolia experienced a pick-up in industrial output as well, although high GDP growth rates had started much earlier, driven by the coal mining industry’s contribution.

Railroad Grand Plan and Current ProgressThe Mongolian government has announced a grand plan to extend the railroad system in a massive project that will connect the eastern and western provinces via the Gobi region. This proposed railroad would run through the major mines in the southern Gobi region, spanning about 1,800 kilometres. According to Mongolian Railway, the feasibility study of this project was commissioned in April, 20114. The cost of the project has been estimated at USD 4-5 billion5.

This project received widespread criticisms, mainly from foreign investors, that it is uneconomical and a result of geopolitics. There has been little update on the progress of this project since 2011, it is not likely that the project would meet its announced schedule, and begin operations by 2017.

Nevertheless, the railroad between the largest coking coal mine (and deposit) in Tavan Tolgoi and the sole buyer in China is very likely to be constructed by the private sector. The Mongolian Mining Corporation (HK: 0975) has been mining a part of the Tavan Tolgoi deposit named UkhaaKhudag since 2009. This company had obtained the permission to build and use the railroad between UkhaaKhudag to the Chinese border for 19 years, and the construction work is expected to finish by 2015.

There are also several companies with deposits in the Khuvsgul province pushing to construct a 682 kilometres railroad extension from Erdenet to Ovoot, through Moron. This group is called the Northern Mongolian Railroad Association, and includes companies such as Aspire Mining and Xanadu Mines as well as the local government. In July 2012, the government of Mongolia announce that the concession to build this extension will be in the “build-operate-transfer” form.

Production OutlookThe future production decisions of Mongolian firms depend heavily on where China’s economy is headed. China’s steel production, which is practically the sole end use of Mongolian coking coal, may pick up steam or cool off depending on China’s policy and other uncertain things. During the 2008 recession, China was able to sail through by boosting its domestic expenditure on fixed investments. Bridges, dams, buildings, roads and high-speed train tracks were built across the nation to inject cash into the economy, hence fill the gap left by the vanishing demands for its manufacturing goods exports.

The quagmire slowdown that began in mid-2011 as a result of the Euro-zone debt crisis has yet to see any relief or realistic route of escape, and the softness or hardness of China’s “landing” is a hot debate topic today. Whether China’s leaders will continue to boost fixed investments, which in-turn boost steel usage, is currently unclear. The other two pillars of China’s economy are domestic consumption and exports. While export is clearly suffering, domestic consumption is slowly but steadily rising. The question is whether consumption rises fast enough to replace the hole left by the falling exports and fixed investments. If no, heavy investments in more infrastructure and construction my yet be necessary to avoid a hard landing. Even if consumption rises quickly, there are other questions that must be answered, such as the source and route of financing of the infrastructure projects.

All in all, it is not likely for the coking coal consumption in China to rise significantly in the near future. However, despite the reduction in GDP growth target, China’s goal of a 7.5% growth is still a very high number. Therefore, we believe demand is certainly enough to sustain the current production level. In particular, as Mongolian coal prices are much lower than seaborne coal, the trend may even benefit the Mongolian producers for a period at the expense of Australian coal producers.

The other limiting factor to production in Mongolia is internal. Currently, the existing rail, paved and dirt roads are all struggling to meet the export demand. The processing centres at border checkpoints are operating all but at capacity. According to the president of the Association of Mongolian Industrial Geologists D. Bat-Erdene, if coal transport roads can be improved sufficiently, Mongolia can easily increase the current production level of about 30 million tonnes per annum by 10–15% . Therefore, even if China’s demand for coking coal continues to rise, infrastructure within Mongolia can be a limiting factor.

The production of thermal coal depends on the demand for electricity in Mongolia, as the relatively cheap price for this product does not justify exports. As the electricity consumption driven by industrial production increases, as planned by the government, more power plants will have to be constructed. The grids in Mongolia have a total ready capacity of 890 megawatts today. The tentative plans for new power stations would add 527 megawatts to this capacity by 20157. The current distribution of capacity as shown in the graph below clearly shows that the bulk of the burden falls on the shoulders of Power Plant #4 in Ulaanbaatar. As the city grows in size and urbanizes, more electricity will be necessary.

Currently, the feasibility study for the Power Plant #5 for Ulaanbaatar area is underway, and the Canadian company Prophecy Coal has obtained the permission to build a power plant next to its Chandgana coal deposit. As of today, no construction has begun yet. If the power plant projects are commenced and completed as announced, Mongolia’s domestic thermal coal consumption will rise much further. The demand for electricity, however, will in turn depend on how economical it is to build mineral processing plants and industrial complexes in Mongolia, which would be the gest users of electricity.

Mongolian Politics and MiningFollowing a peaceful revolution in 1990, Mongolia had a “dual transition” into democratic politics and market economy. Mongolian democracy is young, and has been called into question numerous times. Yet it has proved resilient. It has produced three transitions of power (the last one in June, 2012), essentially demonstrating that democracy is here to stay in Mongolia. So far, Mongolia is the only post-communist country outside of Eastern Europe to successfully have a democratic transition of power.

Mongolia’s democratic politics has perhaps been a double-edged sword, as far as foreign investment is concerned. On the one hand, it has provided the security of a free, democratic country with property rights and a (relatively) fair judicial system. We believe that the chance of an outright expropriation of private property is relatively low in Mongolia. On the other hand, democratic politics has created its own form of uncertainty—governments, parties, and politicians change, sometimes more often than once per four years, and policies can change with them.

The Parliamentary Election of 2012Until the 2012 Parliamentary Election, Mongolia has used a predominantly majoritarian electoral system, which meant, naturally, that two parties dominated Mongolian politics: the Mongolian People’s Party (MPP), formerly known as the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party, and the Democratic Party (DP). In 2011, a smaller faction within the MPP split away from the Party, taking (or keeping) the old Communist-era name of the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP). Led by the former President and Prime Minister Nambaryn Enkhbayar, the MPRP entered into a Coalition with the Mongolian National Democratic Party, which was once allied with the DP.

The Parliamentary Election of 2012 was more favorable to smaller parties (like the MPRP-MNDP Coalition) as it was conducted under new rules: 48 out of 76 seats were allocated through majoritarian rules (but with most districts voting for two or three candidates), and the remaining 28 seats were allocated through party-list proportional representation. As a result, a third party—the MPRP-MNDP Coalition—gained significant influence in Mongolian politics for the first time, winning eleven out of the 76 seats. This victory for the MPRP came after its leader, Enkhbayar, was arrested on charges of graft, and sentenced to four years in prison. The arrest, while hailed by most Mongolians as a victory against corruption, also drew some sympathy for the MPRP from the electorate. Moreover, there were those who said that the arrest was politically motivated; the international press questioned the arrest most suspiciously. According to some observers, this sympathy helped the MPRP-MNDP Coalition at the polls.

Thus during the 2012 Election, the DP gained 31 seats, the MPP 25 seats, the MPRP-MNDP coalition eleven seats, the Civil Will-Green Party Coalition two seats, and independents three seats. The remaining four seats are still contested by the DP and the MPP, since there were allegations of candidates handing out money in two electoral districts (which is against current Mongolian law). The DP was thus forced to form a coalition government with the MPRP-MNDP Coalition and the Civil Will-Green Party.

Platforms and IdeologiesIn theory, the MPP is a “center-left” or a “social democratic” party, and the DP is a “center-right” party. The DP is often referred to as a “liberal” party (in mainly European terms) or a “conservative” party (in mainly U.S. and U.K. terminology).

However, in Mongolian politics, we have found that labels are not especially significant. First, the official platforms that the parties spell out during each election hardly reflect the labels. Second, we could not identify any substantive policy differences in the platforms of the MPP and the DP.

One reason for this could be that Mongolian political parties consist of individuals who are united not along ideological lines, but mainly along personal interests. Here, friendship networks have more influence than ideological persuasion in determining a politician’s party affiliation. Therefore, in each party, we are likely to find liberals and social democrats, resource nationalists and supporters of foreign investment.

Another reason for the lack of major differences in the policies of the major parties is populism, which has largely replaced any principled approach to policymaking in Mongolian politics. Before the 2012 election, gifts and cash handouts to voters were common. In 2008, the DP came up a platform revolving around “One million for every citizen.” That is, they promised to give one million Mongolian tugrugs to every Mongolian citizen. This equates to around 800 USD, and is not a small sum for the average Mongolian. The MPP (then known as the MPRP) responded by promising 1.5 million tugrugs for every citizen. The parties justified these sums on the assumption that Mongolia will soon get wealthy by developing its major deposits, especially the giant coking coal deposit, Tavan Tolgoi. Since then, cash handouts and money promises were outlawed.

Please subscribe to our journal to read more.